About the Observatory

by Bill Georgevich

St. John's College/Santa Fe, NM

The story of Windowpane Observatory really began in 1986 when I co-sponsored an astronomical conference at St. John's College in Santa Fe featuring David Levy and Clyde Tombaugh. I had met Tombaugh as a young man at the age of 16 at a conference at New Mexico State University where he was teaching. I was very impressed with the only living discoverer of a planet and got to spend time with the NASA scope that the university had built, where Tombaugh observed and taught with, as well as his private telescope where he was still looking for planet X, the tenth planet. Tombaugh reminded me that he discovered Pluto with a 13" instrument at a private observatory and that universities became involved in astronomy only in the last 150 years. Tombaugh pointed out that a private facility, like Lowell observatory where Tombaugh discovered Pluto, could produce significant science, especially in the science of astronomical discovery.

[Click image to enlarge] St. John's College was the original proposed site for WPO. The dome that wound up on my Santa Fe private property was to be located on top of the building that's obscured by the tree in the bottom right corner of the picture. The project was suddenly scuttled after the telescope was already completed and the dome ordered. Photo credit: Capt Swing via Wikimedia Commons

Because planning the conference involved consulting with administrators at St. John's College, I developed a personal relationship with the new incoming President of St. John's, Michael P. Riccards. There was a lot of excitement about Riccards because he felt that Santa Feans considered the college and its faculty to be very aloof from the City Different and Riccards was committed to having the college offer its services to the community in the areas of social and economic development and that the college would continue to offer free and nominal-admission events to the public. In the spirit of community involvement and because of the recognition that a basic understanding and practice of astronomy should be part of a liberal arts education at St. John's College—the idea of siting Windowpane Observatory on the St. John's campus was born.

I was to fund the construction and provide the telescope, St. John's would provide the site and utilities at no charge. In addition, I would teach an introductory astronomy class informed by St. John's curriculum. The community-outreach part would be achieved by opening the observatory to the general public for star-parties on warm clear nights during the Summer. Over time a continuing endowment would be sought to pay operating costs including internships for St. John's students. Limiting the scope of the observatory to visual astronomy and the search for transient cosmic phenomena was thought to be appropriate for liberal arts students who did not come to the college to be burdened with complex math and physics. This also kept the budget down for the observatory in terms of expensive instruments like spectrophotometers. Should a new comet or supernova be visually discovered at the St. John's facility, larger observatories could step in and make the necessary measurements.

Since I was funding the telescope and dome I got to choose the visual instrument. I decided upon a f4.5 18" short focus reflector which along with the finest Televue Nagler eyepieces that would yield bright, high contrast visual images for comet hunting and supernovae patrols. The patrols were inspired by the work of visual astronomer Robert Evans, an Australian who holds the world record of 42 supernovae discovered visually. He would later be immortalized by Oliver Sacks in his book An Anthropologist on Mars and Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything.

A 20" or larger mirror was considered but that would require a dome larger than 17 feet in diameter which the St. John's site could not accommodate. The most exciting part of this project for me was using the highly experimental Lanphier Shutter System which theoretically could yield climate controlled observing in the dome. I will discuss this system at length later in the article.

The implementation of the St. John's project proceeded apace for some months. I had acquired the telescope and discussed the novel Lanphier Shutter System with the president of Ash Dome and had looked at a couple of examples used by the DOD at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque. Everything appeared to be a go when Riccards resigned his position for personal reasons and the project was not taken on by his successor.

Because so much was in place—the telescope purchased and operational; the mission of the Windowpane Observatory as a visual astronomical center focused on the identification and discovery of transient cosmic phenomena; the dome and supporting structures drawn by my architect; and an initial deposit made to Ash Dome for the special shutter; it seemed that to move forward to complete the project was a better use of my resources than to abandon it because of internal disagreements within the administration of a college.

Windowpane Observatory's first home outside Santa Fe, NM, in 1988. Photo credit: WPO

Dark sky conditions around St. John's were good. You could easily see the Milky Way anywhere on campus, but the school was located inside the city and subject to local light pollution. Now free of these constraints the dome complex could be sited anywhere. Many interesting sites were considered including Rowe Mesa—a fantastically dark area north of Santa Fe. Ultimately electricity could not be run out to that site at any price and in the end it wound up on 10 acres of land I owned at an ideal dark sky location 15 miles outside of Santa Fe at nearly 8,000 ft. above sea level. Because the Lanphier Shutter was so rarely purchased from Ash Dome, the president of the company offered to fly out to Santa Fe to supervise the construction by my general contractor.

WPO Tests Climate-Controlled Visual Observing

Despite the loss of an academic environment there still remained the very important testing and data collection of the Lanphier Shutter System. Could you view visually through a large aperture telescope through optical glass with large temperature differentials? The high altitude Santa Fe location was the perfect atmospheric test bed. This was the main function of the Santa Fe location. Inside the bottom floor of the observatory cylinder was a 10,000 BTU heating system that was capable of heating the dome to 70 F. while the outside temperatures were below 0. Would heat radiating off the glass distort the image? Would fans have to be installed on the outside to disperse this heat? Would the additional glass reduce the apparent magnitude of objects or distort them?

Visual astronomy through the glass proved to be flawless up to about 300 power. At 60 power there was no noticeable image distortion and a very slight reduction in apparent magnitude. Pointing the telescope through the glass was similar to the glass at the front of a Schmidt–Cassegrain catadioptric telescope.The only critical factor was getting the Lanphier glass plate exactly parallel to the primary mirror-something that had to be done manually for each object. After a few observing nights the approximate position of the Lanphier Glass became intuitive and it only took a few seconds to find the exact sweet spot.

After successfully observing night after night with various associates acting as telescope operators, I prepared a number of lectures of which these slides were part of the presentation. No one attending those lectures ever went to the expense of getting a dome shutter system like this although I noticed the Lanphier Shutter System was showcased in a 2013 Youtube video which I have included here.

Here are the never been seen before on this web site 35 mm slides of the dome and dome tower complex right after completion. The dome had to be placed on a 14 ft. tower to clear the pinon trees indigenous to the area.

This first slide shows the completed dome tower with the Lanphier Shutter closed and operational under hostile weather conditions like cold and wind.

The dome is completely closed with the window in the down (Horizon) position. Photo credit: WPO

The next three frames illustrate how the shutter moves up toward the zenith, completely enclosing the observer.

The Lanphier Glass Viewing Port is at a 20° elevation. You can see the bottom of the shutter enclosing the observer below the glass. The rectangular box in front stores the bottom of the shutter assembly which is detachable. Photo credit: WPO

Here is a slide showing the viewing port elevated to a 45° angle. Photo credit: WPO

Here is the Lanphier Glass Viewing Port close to the zenith. As you can see there is enough shutter assembly in the shutter box to raise the glass as high as you need (even slightly past the Zenith position). Photo credit: WPO

Next we have a shot through the Lanphier glass to show its transparency, followed by a couple of technical slides about how the shutter assembly attaches to the "windowpane" from which the observatory gets its name.

Here is a shot out of the Lanphier Window taken from inside the observatory. This is what the telescope observes through. Photo credit: WPO

This is what it looks like from the inside when the shutter is closed and a telescope is peering through the glass. Photo credit: WPO

Detail shot showing where a set pin is located that serves to attach or detach the bottom of the shutter assembly from the viewing glass. Photo credit: WPO

The pane can be left at the bottom of the dome for open-air observing or the pane can be hoisted to the zenith for open air observing along the visible horizon.

Here is a slide of one of the WPO telescopes looking through the slit with the window parked below where the telescope is pointed. Photo credit: WPO

Windowpane Observatory functioned successfully with the Lanphier Shutter for 2 years until an opportunity arose to move the facility to an extreme Southern Arizona location featuring 335 clear nights per year—most of those nights being moderate in temperature.

Moving Windowpane Observatory to Southern Arizona

When I say clear skies 335 days a year, I mean that sometime during the night, the sky will be completely clear. Southern Arizona has many noted observatories scattered on various mountain tops—the most notable being Kitt Peak the National Observatory of the US. I was looking for a darker site than Kitt Peak as it is only 40 miles south of Tucson and Tucson is a much bigger city now just as LA and San Diego are much bigger now than when Palomar Observatory was constructed. After spending a couple of years scouting and testing locations, I settled on an area adjacent to Organ Pipe National Monument.

The most important directions for observing are the East and South. The South is the limit to what you can see from your position in the Northern Hemisphere. The East is where the newest part of the sky is visible. "If you're hunting comets and want to beat the competition then you better being looking East before someone else sees the new object first." That was the advice I received from veteran comet hunter and discoverer David Levy.

Having focused on the area and environs around Ajo, AZ—30 miles North of Organ Pipe, 58 miles north of the Sea of Cortez, 108 miles southeast of Phoenix and 127 miles southwest of Tucson—you would think it would be easy to site the observatory with all that available open desert. As I began negotiating with various land-owners I found that not to be true at all. Some government held BLM land was restricted and not available. There was Radar Hill which sat on top of a small mountain outside of Ajo. A small unimproved road led up to the top of a radar facility used for the Barry M Goldwater Bombing Range, which sat in the middle of the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge. My observatory site committee had a number of meetings with the Refuge Director. In the end he declared increased traffic from visitors to the observatory would disturb the wildlife in the refuge. After they are built, astronomical observatories have a very low environmental impact. Observatories don't use water and astronomers don't want land improvements. They want things undeveloped, pristine, and dark. None of us on the committee could understand the director's intransigence.

A lot of privately owned land were abandoned mining claims. One perfect spot south of Ajo blocking all its local light pollution with dark, dark views South and East, was a mining claim. I told the owner I don't want the mineral rights I just want to place my dome on his property along with a caretaker living in a trailer next door for security reasons. The owner was only interested in selling me land with mineral rights which he appraised at a much higher cost than the entire observatory complex. Consequently we didn't site there and to this day no one has ever mined any copper there—the site is still pristine. All these leads were graciously given to me by Jim Armstrong, the manager of the Ajo Phelps Dodge Mine which built Ajo. The mine was now closed and the concomitant air and light pollution was gone from the area making it very dark once you left town.

A still smaller town, by the name of Why—so named because it is actually a Y in the road on the way to Organ Pipe Natl. Monument—was also offered by an ad hoc committee that approached me about siting the observatory even further south closer to the international border. Unfortunately, they wanted WPO to investigate UFO's as there were many sightings down there. After several meetings I told them that SETI was much more qualified for this kind of work and they should support them. WPO wanted to keep it's original mission that we established at St. John's—the search for and discovery of transient cosmic phenomena. It was starting to look like despite this vast, unoccupied desert with its pristine dark skies, there was no one willing to give a home to Windowpane Observatory. Sitting in Jim Armstrong's living room bemoaning this fact on a dark clear night, Jim suddenly said "Let's get in my car. I've got the perfect place."

Where we wound up was indeed a spot that was pitch dark both in the East and South, yet we were still on the south side of town. Standing in the parking lot of the mining museum we were facing the abandoned copper mine which, of course, is abandoned and uninhabited. Jim pointed out that it met all my requirements. Dark in the 2 most important directions with electricity and phone. And I realized since it was in town it would be the only observatory 5 mins from a Circle K! As long as I agreed to a 30 day month to month lease and Phelps Dodge retained the mineral rights underneath I could build the facility here with the understanding that if Phelps Dodge ever reopened the mine they had the right to take the land-use away from me within 30 days. Since I didn't think the mine would ever reopen I wasn't worried about it. What I was worried about was the adjacent light pollution from bright high pressure sodium vapor lamps to the West and North.

International Dark Sky Association

The serendipity that made this the new home for Windowpane Observatory possible was two men I had just met. Tim Hunter and David Crawford were founding the International Dark Sky Assoc. I had attended a meeting where several cardinals dressed in red were present to talk about the new Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope observatory being built on Mount Graham, AZ. Galileo, over 400 years later, had finally been forgiven by the Catholic Church for his transgressions and the Holy See was embracing astronomy with new vigor. At the time they were dealing with environmentalists who claimed a little red squirrel was being threatened by building the new facility on Mount Graham and smart-alecky astronomers were drawing cartoons of those squirrels sitting in lounge chairs wearing sunglasses nibbling on peanuts and other food left by astronomers as they looked through the telescope. At that meeting I promised to get involved with the IDA to get cities and towns to switch to low pressure sodium 90° full cut-off fixtures that pointed light only down.

David Crawford was a prominent astronomer at the largest telescope at Kitt Peak—the Mayall Observatory and it certainly was in his best interest to limit the encroaching light pollution from Tucson. But what Tim and David were also playing with was the idea of rewarding municipalities that embraced their anti-light pollution practices. The next time I met with them I proposed that perhaps Ajo could be "America's First Dark-Sky City". Dr. Crawford agreed to help me sell the idea to Ajo officials and agreed to appear as a featured guest in Dicus Auditorium of the only high school in Ajo at a special meeting to promote Ajo as an astronomical home for Windowpane Observatory and a travel destination for astronomy enthusiasts.

Phil Mahon an associate of mine in Las Vegas, New Mexico had pioneered the concept of an astronomical bed and breakfast under very dark skies, calling it the Star Hill Inn complete with telescopes. The problem was, his dark sky location has lots of snowstorms and cloudy nights. A similar model in Ajo would have clearer skies, a great climate Fall through Spring and more amenities—if, and that's a big if, if the city lights could be converted to the IDA standard.

With the complete support of the IDA, I found a manufacturer to provide the street lights that met the IDA's strict specifications. Our Ajo Dark Sky Committee then found the funding to replace the high pressure sodium lights with the 90° full cut-off low pressure sodium box-type fixtures. Ajo Improvement which is one of the two local providers of electricity was more than happy to provide the free labor to replace the street lights since the new fixtures used much less electricity making their long term use very economical.

Once I was confident that the funding was going through I committed to moving the observatory to Jim Armstrong's suggested site. Just as the Santa Fe site was a test bed for the Lanphier Shutter and climate controlled visual astronomy, the Ajo site would now be an initiative for fighting light pollution and taking back our dark skies that were lost from inappropriate lighting.

Ajo, AZ in the 90's was a hotbed of experimental and alternate living ideas. The unincorporated town meant little regulation and all kinds of projects came to town that were either just rumors or incomplete. My favorite was a company that built underground homes. Because the temperature underground is a steady 57 F. building a house in Ajo where there was one floor underground would mean that if you were willing to spend the majority of your time during the Summer underground there would be no air conditioning cost. The company built a couple of model homes using army surplus materials but then abandoned the project. And so it was believed that WPO coming to Ajo was a hoax. So when the crew and truck appeared we were joined by a lot of townsfolk photographing and chatting with the crew. Some offered to help, but due to the precise nature of the work all they really could do was cheer us on and offer us refreshments.

It was very important to dismantle the dome at the Santa Fe site before the first snow which could easily make roads impassable as early as October. And so the deconstructed dome arrived in Ajo on September 30, 1991. My crew that erected the facility in New Mexico traveled with the truck since they knew how to put it together. And I had an Ajo crew that prepared the site for the dome. Since there are no trees to clear in the desert, the dome would not require a cylinder and the observatory could be entered through the slit. This reduced my costs since the cylinder did not have to be re-erected and made getting people in and out of the observatory, especially large school groups, easier and safer.

Building the Observatory in Ajo, AZ

[Click image to enlarge] This is a wide shot of the site. Enlarging this image reveals the observatory foundation to the right of the old mission church. You can see how the mine and mine tailings eliminate all human housing and its attendant local light pollution. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

This slide shows the concrete slab, block foundation, suspended wooden floor, and 2 foot square cut-out for the telescope tube assembly. All this was prepared before the dome arrived. The telescope pier is completely isolated from the suspended floor so that vibrations from the floor are not transmitted to the telescope. Because the heavily carpeted floor is suspended above the alt-azimuth axis of the telescope, a ladder is not required at any viewing angle. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

The steel circular track on which the observatory rotates is now being added to the wooden under-structure. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

To the left of the assembly man is one of 2 electric dome motors. Further left is the long rectangular steel box that contains the entire shutter assembly that can be locked to the bottom of the viewing glass with large set pins. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

Like a giant Erector Set, the first strut is attached. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

More struts are added one at a time. The tolerances to keep the dome level and rotating and the shutter raising properly up and down are very high. Photo credit: WPO/Jerry Van Wyngarden

The redesigned and re-purposed observatory relocated from Santa Fe as it appeared in Ajo after completion in 1991. This image was scanned from a Ajo Chamber of Commerce Brochure circa 1992. Photo credit: Jerry Van Wyngarden/Ajo Chamber of Commerce

The funniest thing that happened during the erection of the dome in Ajo was that a freak heat wave had raised temperatures that week to 111° F. My Santa Fe crew and General Contractor said, 'Bill, you did not move the dome to Paradise you moved it to Hell." It was so freakishly hot we had to put their tools in ice buckets to keep them cool. Nonetheless the installation went flawlessly and WPO now had a much better overall climate, more clear nights, strip parking for large events, not to mention being 5 mins from a 24/7 Circle K convenience store if you needed coffee or sweets to stay up all night.

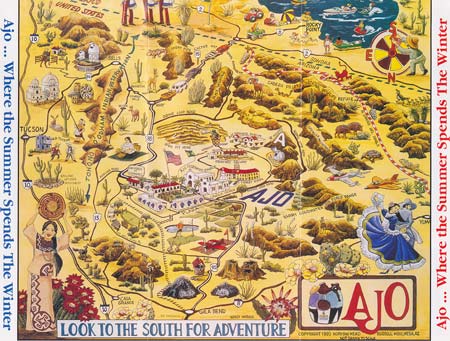

[Click image to enlarge] Here's the fun caricature of Ajo that includes WPO and Kitt Peak. Even though the distances and sizes are distorted, this map accurately describes the town and the surrounding area. You can even see the Sea of Cortez to the south that provides WPO with such dark skies. Photo credit: Norman and Russell Mead/Ajo Chamber of Commerce

To celebrate the IDA lighting and the new facility, the Ajo Chamber of Commerce put out a new brochure featuring WPO and created one those cartoon maps of the town showing 2 observatories—Kitt Peak and Windowpane. I found a copy of those old brochures and scanned it to show the caricatures of the two telescopes being the same size, which the Chamber explained was fair game since it was a caricature and they were trying to promote the town. Thousands of those brochures were mailed and passed out and fortunately no one was disappointed when they discovered an 18" telescope In Ajo as opposed to a 158 inch on Kitt Peak!

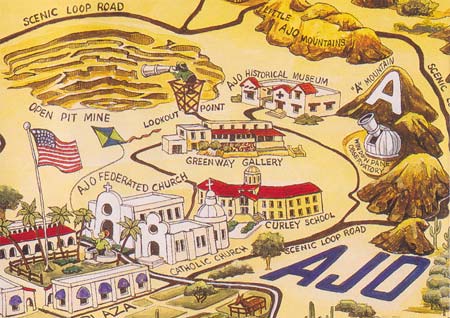

[Click image to enlarge] Here's a close up of the immediate area around the observatory. A Mountain blocks light from the town of Ajo. The observatory faces the copper mine pit, yielding a very dark South and East sky. All the street lights in this area were converted to low-pressure sodium 90° full cut-off fixtures. Photo credit: Norman and Russell Mead/Ajo Chamber of Commerce

This was not this funniest thing ever to be associated with Windowpane Observatory. In the early 90's the Internet was already a significant network for getting scientists to speak to each other. By 1994 Netscape Navigator became the first browser to receive universal acceptance. And so I decided that Windowpane Observatory needed a web site. First I had to get a domain. During those days before search engines were prominent you wanted a very short 3 letter domain like NBC.com or ABC.net or NSF.gov which was the National Science Foundation that issued domains. Except you couldn't go to their web site and get a domain you had to fax the NSF and hope they would grant your request.

I knew what 3 letters I wanted WPO for Windowpane Observatory. It reminded me of a stock ticker number like TWA for Trans World Airlines. There was a .gov domain extension for the government, .edu for universities, .com for businesses, .net for networks, and .org for non-profits. Since we were no longer associated with St. John's College, we were not eligible for the coveted .edu, and since WPO was not a government agency, .gov was not applicable. That left .com, .net, and .org. I had not set WPO up as a non-profit because it was a private facility and I didn't want to be saddled with all the paperwork. This was a time when it was not so easy to be a non-profit as it is now.

So I decided on .com, which was the best known domain extension and was universally applicable. Unfortunately WPO.com was already used by the World Presidents' Organization. Since I was not the president of any country (large or small), that left .net. I wrote a mission statement about Windowpane Observatory that I included with my wpo.net domain application to the NSF. It said:

"You can identify an astronomer by the fact that whenever they step out the door at night, they look up. To understand and be oriented to the night sky is far more than merely educational. Finding your place in the universe gives every human a cosmic perspective on their life and its relationship to time and space. I believe that a human being cannot fully grasp their existence without this knowledge and experience. Expanding one's awareness beyond the confines of this planet gives us the cosmic perspective to cope with our daily problems here on Earth. It's my intention to actively share this perspective with others."

Then there was calling them repeatedly waiting to receive the domain while we built the web pages. I wanted to make the web site a general educational web site about science and astronomy, So many people confuse astronomy with astrology. I was often called an astrologer by my own students! I wanted to avoid the cumbersome mathematics of physics books but at the same time showcase the excitement of pure scientific discovery for science's sake. The original site had the following departments which still form the basic framework of wpo.net today:

Astrotales—Astronomers are characters whether you are talking about observational astronomers like Edwin Hubble or theoretical astronomers like Albert Einstein. They may be boring and tedious nerds in the lecture hall, but their private lives are funny, controversial, and often extremely interesting and unusual.

Ask the Astronomer—What better way to utilize the new medium of the web than to invite visitors to email wpo astronomical questions that we can answer and in some cases, if the questions were interesting, publish on the web site.

Astronomy 101—A very popular page of commonly used terms in astronomy that are easily explained without the math

Credits—A little bit about me as the director of WPO and a page that credits various photographs either used with permission or public domain.

Articles and Astronomy News—Since WPO was dedicated to the discovery of and information about transient cosmic phenomena this was the "front page" of the web site. Here we would discuss upcoming eclipses of the sun and moon, transits of the Sun by Mercury or Venus, new or returning comets and asteroids, as well supernovae like 1987a—a type II supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud easily visible with the naked eye at 3rd magnitude.

By the time all the web pages were completed we finally got an answer from the NSF: "Yes, your domain wpo.net has been granted." We sent them a check for $600 and the domain became active.

To see the night sky observing forecast for WPO in Ajo, click on this link. Photo credit: A. Danko

These were heady days for the observatory. We immediately got ranked on a new web site called cleardarksky.com for our incredible 5 of 5 rated clear skies. When the Yahoo search engine debuted we were right there with all the other major facilities that started with W. But we still needed something to bring pizzazz to our main mission—teaching and popularizing astronomy for the "civilian" web visitors who were curious about astronomy but knew nothing about it. What could we do to bring ourselves that kind of publicity and attention?

NAME A GALAXY

One visiting astronomer to the facility showed me a certificate. "I bought this star for my wife. She loves it. I got it from the International Star Registry. Even though we know the star's SAO number will remain unchanged and the name we see on the certificate will never show up on the Palomar Sky Survey or any other astronomical chart, I can point it out to my wife and she liked the pretty certificate so much she put it up on the wall in her office! When her office mates saw it they registered a star in their name as well."

Why would folks be interested in such a thing? What I found out was that it allowed them to make a personal connection with the cosmos even if it did not have any scientific value. Like adopting a stretch of highway or naming a dolphin, it was the gesture that connected them.

So what if instead of personalizing a star, we registered galaxies—billions of stars? And what if we chose galaxies that had a bright enough apparent magnitude to be visible in a backyard telescope, say an 8" to 10" reflector? And instead of just sending them a pretty certificate, what if we included a scientific profile that told them the exact right ascension and declination position of what they named along with its apparent magnitude, size in arc seconds, galactic morphology, and constellation it could be found in? And instead of a star chart with mythological figures superimposed on the constellations, we sent them a real planisphere they could use to learn their constellations and star hop to various objects? In other words, the galaxy naming certificate would actually be an "introduction to visual astronomy kit". What if each galaxy adopter could call the WPO telephone number and get their astronomy questions answered, not only about the galaxy they registered, but any other astronomy science question? In other words, each registrant would be like an underwriter of WPO, funding the educational parts of the web site as well as helping with the overhead of the telescope. And finally, instead of registering objects in a private registry like the International Star Registry where nobody could see it, what if the galaxy registry of WPO were published on the World Wide Web so that anybody could look it up there?

And so around Christmas time of 1995, we constructed the Name a Galaxy section of the wpo.net web site. We did some advertising in print and on the radio, but the only galaxies we registered were ones that we did for free. We put a disclaimer on the registry page, which said:

Windowpane Observatory has established on the World Wide Web a registry of names for galaxies in the universe that were previously unnamed. The vast majority of galaxies in the perceivable universe have no names. Of course, for astronomers this does not present a problem, since physicists refer to celestial objects by their astronomical catalog number.

These numbers, along with the celestial coordinates, are then input into the targeting computer of the telescope, and the instrument automatically slews to the object. For example, the most famous galaxy outside the Milky Way is the Andromeda Galaxy, named after the constellation Andromeda in which it is found. But astronomers refer to the Andromeda by its catalog number. In the Messier Catalog of objects, Andromeda's catalog number is M31. In the New General Astronomical Catalog, Andromeda's catalog number is NGC 224. So on the one hand, a heretofore unnamed galaxy will still be referred to by astronomers by its number depending on what catalog is employed. The naming of celestial objects does not change either their generic name nor their SAO number, NGC number, or other catalogue number. On the other hand, these anonymous galaxies containing black holes, supernovae, open and globular clusters and billions and billions of stars will now be named in this registry.

It looked like there was no interest in my galactic registry idea and certainly a dead end for any underwriting. Every year the International Star Registry does a big ad campaign around Valentine's. "Register a star for your sweetheart." I decided to call some area newspapers and see if anyone would like to interview me about my galaxy idea that I was launching on the World Wide Web. Finally, a feature writer for the Arizona Star, a Tucson morning daily newspaper, agreed to a phone interview. He was very kind and respectful and I explained to him that like the International Star Registry we make it very clear that the galaxy is only named in our registry and will not affect star charts used by scientists. He told me the article would come out a few days before Valentine's and he would email me a copy. I received the advanced copy on Thurs. Feb. 8, 1996. It was a scathing hatchet job. Dismissively making fun of the name a galaxy concept, ignoring my clear disclaimer that this was a way to introduce folks to astronomy while maybe raising a little money, the reporter eviscerated me and my project as phony and without merit. I thought, well it worked for the Star Registry, but not for WPO. The Star Registry had no scientific component. It was just pretty pictures and fancy certificates. Perhaps we couldn't mix real science with people's desire to name a celestial object, even though I knew of several planetarium name-a-star campaigns that raised money for their facilities. Perhaps that fantasy didn't mix with a hard science web site.

We had established a dedicated phone line for the observatory with call waiting, and I figured I'd get a number of harassing phone calls when the paper was delivered on the morning of February 9th when the article came out. At 4:50 am that morning, the observatory line rang for the first time. "I'd like to register a galaxy please." How did you find out about our program? I asked. "The article in the Tucson paper." But that article criticized the whole idea heavily. "Oh, we went to the web site and read all about it. We think it's a lovely idea. Can I register more than one?"

By 6 am that morning, the phone was ringing continuously. I called the phone company and had 3 more landlines put in that day so that we could call people back on other lines. We asked each caller how they heard about us. It turned out that the article had gotten onto the AP wire and was reproduced in 44 newspapers that day. But the AP version was based on reporters going to our web site and forming their own opinion about the name a galaxy program, and their articles all praised it for the same reasons I thought it was good idea. Suddenly WPO was living proof of the adage "there's no such thing as bad publicity". In this case, the subsequent stories that made it into the dailies of major cities like Chicago, New York and LA were actually positive versions derived from reporters reading the web site. I also realized that papers loved having a fast-breaking news story that they didn't have to call WPO for an interview. They could just look us up at wpo.net and write their story based on the info they found there. The Internet was proving itself to truly be an alternate way of delivering information.

We were overwhelmed with registrations. So much so that we overwhelmed the nearest FedEx office with all the packets that our registrants wanted on or before Valentine's Day. By Feb. 10, CNN had called requesting permission to send a film crew to interview us about the national phenomenon. What really surprised us was we were getting a lot of referrals from other observatories like Kitt Peak, Palomar, Lick, and Yerkes—all much older and very much bigger facilities than our 17 ft. dome housing our telescope that is a little more than a 1/2 meter in diameter. In the end, the story became the story about the story—folks naming galaxies as part of their wedding engagement, celebrating the birth of a child, or cheering up the seriously ill—the cosmic perspective was truly magical for a lot of our callers. On Feb. 13th, the Phoenix CNN affiliate aired a completely complimentary special about us on the 10 o'clock news opening with the Star Trek—Final Frontier intro to the original Star Trek TV series. Later, because of that, we were invited to a major Star Trek convention in Phoenix, where we went on stage with original and Next Generation Star Trek stars to talk about our program and make special awards and presentations.

People loved the galaxy package. They asked us about the science. Those that didn't have telescopes used the star charts we provided to show their families where in the sky the galaxy was that they had named. And amateurs used our RA and Dec coordinates to find and photograph their registered galaxy with their backyard telescopes. Because we had been so transparent about the conceit, and because we really could talk about galaxies and astronomy in general with depth and authority, we had proved that entertainment and hard science could stand side by side on the web. And my dream of using such a convention to entice folks into "finding your place in the universe", to be curious about real science and to wonder about the cosmic perspective and take a break from their Earth-bound lives, seemed possible.

Live Celestial Special Events at WPO Underwritten by our Supporters

Although we did not have the detail of this HST photograph from space, at WPO we were able to see each of the dark spots pictured here and hoped they would fill in so that Jupiter could survive unscathed. Photo credit: NASA/Hubble Space Telescope

Even though the moneys raised were hardly comparable to that of university endowment, the registrations did fund a number special events and conferences. After meeting David Levy in 1987 who introduced me to Gene and Carol Shoemaker, I asked him why he was so much more interested in comets rather than supernovae—which was my research concentration. He told me that comet discoverers get to name comets after themselves and supernovae just got a new number. "If I discover a really important comet, you'll see it on the cover of Time magazine!" Not only did comet Shoemaker-Levy make the cover of Time, but the cover story featured pictures of David Levy himself—propelling him to the forefront as a cometary astronomer even though his degrees are all in the liberal arts. (He is now Senior Editor at Sky and Telescope) I mention this because the largest event we sponsored at WPO before the galaxy fund-raiser was the live visual observation of the Shoemaker-Levy impact.

We knew the size of the comet and that Jupiter's gravity had broken the comet apart into various smaller pieces. What none of us that night expected was for there to be visible "holes" in Jupiter's atmosphere clearly visible in the telescope. I turned to my associates and mentioned that planetary astronomers had given the comet a 10% chance of the comet destabilizing Jupiter in some way which of course would be catastrophic for the entire Solar System since Jupiter is the largest body outside of the Sun. These multiple holes lasted several hours and I told my group, "If they don't fill in." this is going to be the biggest Armageddon Story since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Fortunately in the end no harm was done to Jupiter. But this transient cosmic event proved to me how the public could be included and riveted by an astronomical event—a cosmic occurrence we could visually observe in real time, report on, and share with anyone interested in attending our events.

What made Comet Hyakutake so special was that it was crossing through the circumpolar constellations of the Northern Hemisphere. In this picture, note that every image is curved except for the one star around which all the stars turn, Polaris. Photo credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

The funds we raised with galaxy registrations allowed us to put on a number of special events surrounding other transient phenomena. Comet Hyakutake appearing in March 1996 just one month after the name a galaxy media explosion was the first event funded by registrations. Stretching its blue tail across the circumpolar constellations, Hyakutake was a spectacular object, both through binoculars and telescopes.

The most spectacular object that WPO hosted multiple events for was Comet Hale-Bopp, discovered by a New Mexican and Arizonan respectfully and coincidentally the 2 states in the US that Windowpane Observatory has been based in. Many star parties were arranged both at the observatory and all over dark sites in Arizona-funded and organized by WPO. Hale-Bopp was so bright, you could see it in downtown Phoenix!

The twin tails of Hale-Bopp were visible from WPO for months. This long exposure photograph showcases the blue ion tail and the yellowish sodium tail. This is what we saw at WPO, along with the total eclipse of the Moon and the close approach of Mars, all in one special evening. Photo credit: Giuseppe Donatiello.

The apex event for us at WPO was a visual astronomical conference that featured looking at Mars on close approach to the Earth, a total lunar eclipse whereby observers could watch the curved Earth's shadow cover the rills and craters of the moon in real time, and then during totality allowed attendees to enjoy the Milky Way and all its splendors while the Earth's shadow covered the moon, plus Comet Hale-Bopp—all in one evening of observing!

Because I'm also a musician and the acoustics of the dome are quite unusual and interesting to play with, we hosted a number of musical retreats called The "Music of the Spheres" Series, inspired by Johannes Kepler's book of the same name that proved that the planets revolved around the Sun not the Earth. With the dome closed, musicians would play their compositions inspired by the NPR program Hearts of Space, and as the red lights in the floor of the dome slowly dimmed down to absolute darkness, fully night-adapting their eyes, I opened the dome giving those inside the sensation of opening a porthole on a spaceship since the only thing you could see were stars, planets, even the Andromeda Galaxy naked-eye in a sea of darkness.

The author and founder of WPO celebrating the completion of Windowpane Observatory at the first Santa Fe dark-sky site—a few hours before dusk and First Light. Photo credit: WPO

The 1990's were truly the apex of constantly expanding activity for WPO the facility and WPO the web site. But the aspects that made WPO so unique; as an Internet educational tool and its physical location as a guest of a mining company brought massive and sometimes unwanted change in the new Millennium.

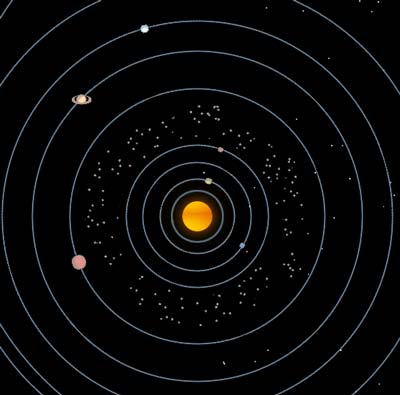

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system.

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system. See amazing views from space

See amazing views from space