Populating Google's Sky

Astronomers Eager to Add to Google Sky

by Robert Sanders

9/7/07

Since Sky in Google Earth debuted two weeks ago to let the public explore the heavens from their computers, two University of California, Berkeley, astronomers have jumped in to populate Google's sky with the most recently discovered celestial objects.

For Google Sky's Aug. 22 launch, Professor Geoffrey Marcy and his international planet hunting team provided Google with coordinates of all the stars with known planets - more than 200 planets around nearly as many stars.

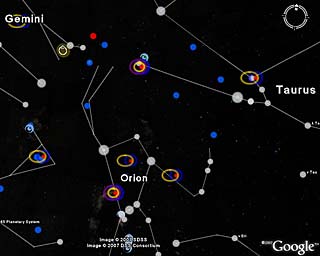

The piece of the sky in Google Sky, pictured right, shows 7 planetary systems around nearby stars (blue & gold ovals) and a recently discovered gamma-ray burst in the constellation of Gemini (diamond-ring object). By clicking on these icons, Google Sky users can pull up detailed information about exoplanets and sudden flashes of light in the sky.

This week Google posted on its Web site another layer of information users can add to their personal sky: real-time updates on new objects that flash in the heavens. According to Joshua Bloom, a member of the team that prepared this layer, it is a combination, or "mash-up," of new data on exploding stars, called supernovae; extremely bright and energetic flares called gamma-ray bursts; and peculiar brightenings of stars, called microlensing events, caused when starlight is bent around a nearer star and magnified. Gamma-ray bursts are spectacular explosions arising after the death of massive stars as they collapse to produce black holes.

"Right out of the gate, Google Sky has become a powerful tool for the public and in the classroom," said Bloom, an assistant professor of astronomy who employed Sky in his opening lecture last week to an introductory astronomy class at UC Berkeley. "And if it works well and gets more and more of these transient events into the system, we as researchers will be using it."

Bloom and his colleagues at the California Institute of Technology and Los Alamos National Laboratory build the "cyber"-infrastructure, called VOEventNet, that allows satellites and telescopes to send astronomers, and Google, real-time information on these newly discovered transients in the sky.

"We set out to create a language that can be parsed by computers, so computers can talk to one another," telescope to telescope, Bloom said. "VOEvent is an important backbone for the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which should detect thousands of interesting transients every night. With that amount of data, we need something like this to do real-time astronomy."

The LSST is a proposed ground-based 8.4-meter telescope that will image faint astronomical objects across the entire sky, returning night after night to some of the same objects. Targeted for completion by 2017, the telescope would allow the study of objects - supernovae, potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroids, and distant Kuiper Belt Objects - that change or move on rapid timescales.

"LSST answers the question, How do you do 21st century astronomy?" Bloom said. "The cutting edge won't be people going to telescopes and taking data, but terabytes and terabytes of data coming in every day, and astronomers sifting though the data for new discoveries."

Until this new era arrives, Sky in Google Earth provides a taste of what's in store for astronomers, and Google seems pleased by astronomers' response.

"We have seen astronomers embrace this service because of the potential it has to serve as a platform for sharing astronomical data," said Google's Ryan Scranton, one of the developers of Sky. "This is a very grass roots, ground-up effort."

When first launched two weeks ago, Sky in Google Earth allowed users to navigate the sky to find hundreds of millions of stars, to view Hubble Space Telescope images of beautiful galaxies and nebulae, to focus in on star fields mapped by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and to display the constellations, moon and planets. With Marcy's data, they also were able to chart the locations of exoplanets discovered by him and his California and Carnegie Planet Search team.

As of this week, Bloom and his team began feeding Google a mash-up of gamma-ray bursts discovered by NASA's Swift orbiting observatory and the Milagro ground-based observatory; microlensing phenomena detected by the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), which searches for dark matter within the Magellanic Clouds and the Milky Way's galactic bulge; asteroids and optical transients from the Palomar-Quest survey; and newly exploded supernovas from surveys by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Supernova Search and ESSENCE. The mash-up is updated every 15 minutes.

VOEventNet, which allows these disparate data to be fed to Sky, was developed with funding from the National Science Foundation as a way to automate astronomy so that new observations are relayed within seconds or minutes to robotic telescopes that can quickly and automatically swivel to observe them. Today, such discoveries are announced to astronomers through email or fax "telegrams" from the International Astronomical Union, often delayed for days while referees assess the event. VOEventNet would eliminate the middlemen.

Sky in Google Earth provides one way astronomers and the public can see now the amazing objects being discovered daily by telescopes and orbiting satellites. Bloom expects more astronomers to take advantage of the ease of adding mash-ups to Sky in Google Earth in order to layer interesting astronomical objects over the viewing area and create personalized tours of the cosmos.

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system.

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system. See amazing views from space

See amazing views from space