20 Light Years Away, the Most Earthlike Planet Yet

by Dennis Overbye

4/25/07

The most enticing property yet found outside our solar system is about 20 light years away in the constellation Libra, according to a team of European astronomers.

The astronomers said Tuesday that they had discovered a planet five times as massive as the Earth orbiting a dim red star known as Gliese 581.

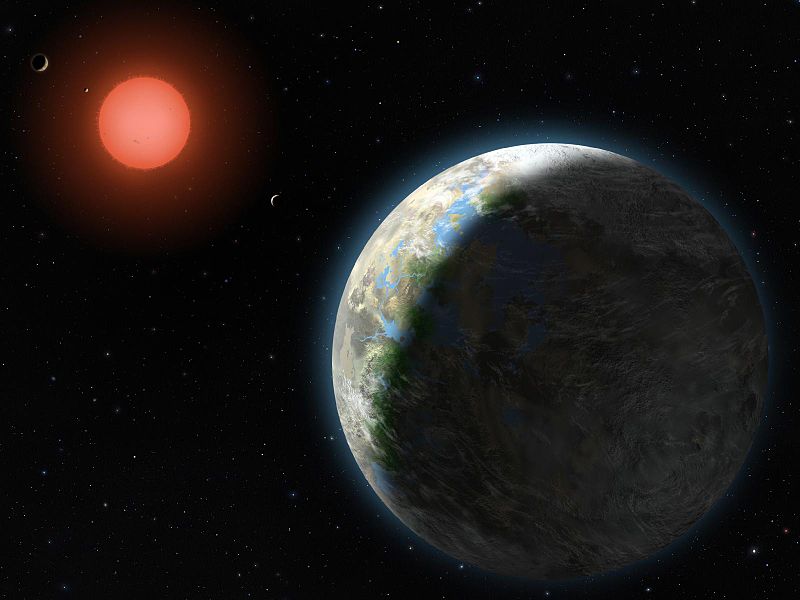

An artist's illustration of the planet designated Gliese 581g.

© NASA/Lynette Cook

It is the smallest of the 200 or so planets that are known to exist outside of our solar system, the extrasolar, or exo-, planets. It orbits its home star within the so-called habitable zone where surface water, the staff of life, could exist if other conditions are right, said Stéphane Udry of the Geneva Observatory.

"We are at the right place for that," said Udry, the lead author of a paper describing the discovery, which has been submitted to the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

But he and other astronomers cautioned that it was far too soon to conclude that liquid water was there without more observations. Sara Seager, a planet expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said, "For example, if the planet had an atmosphere more massive than Venus's, then the surface would likely be too hot for liquid water."

Nevertheless, the discovery in the Gliese 581 system, where a Neptune-size planet was discovered two years ago and a planet of eight Earth masses is now suspected, catapults that system to the top of the list for future generations of space missions.

"On the treasure map of the universe, one would be tempted to mark this planet with an X," said Xavier Delfosse, a member of the team from Grenoble University in France, according to a news release from the European Southern Observatory, a multinational collaboration based in Garching, Germany.

Dimitar Sasselov of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who studies the structure and formation of planets, said, "It's 20 light years. We can go there."

The new planet was discovered by the wobble it causes in its home star's motion as it orbits, using the method by which most of the known exo-planets have been discovered. Udry's team used an advanced spectrograph on a telescope measuring 141 inches, or about 360 centimeters, in diameter at the European observatory in La Silla, Chile.

The smallest exo-planet found previously was roughly six Earth masses, found by a team led by the American planet hunters Geoffrey Marcy of the University of California, Berkeley, and Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. They are longtime rivals of the Swiss group founded by Michel Mayor of the Geneva Observatory.

The planet, officially known as Gliese 581c, circles the star every 13 days at a distance of about seven million miles, or 11 million kilometers. According to models of planet formation developed by Sasselov and his colleagues, such a planet should be about half again as large as the Earth and composed of rock and water, what the astronomers now call a "super Earth."

The most exciting part of the find, Sasselov said, is that it "basically tells you these kinds of planets are very common." Because they could stay geologically active for billions of years, he said he suspected that such planets could be even more congenial for life than Earth.

Although the new planet is much closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun, the red dwarf Gliese 581 is only about a hundredth as luminous as the Sun. So seven million miles is a comfortable huddling distance.

How hot the planet gets, Udry said, depends on how much light the planet reflects, its albedo. He estimated that temperatures on the surface of the planet should be in the range of 0 degrees to 40 degrees Celsius (32 degrees to 104 degrees Fahrenheit).

"It's just right in the good range," Udry said. "Of course, we don't know anything about its albedo."

One problem is that the wobble technique only gives masses of planets. To measure their actual size and thus find their densities, astronomers have to catch the planets in the act of passing in front of or behind their stars. Such transits can also reveal whether the planets have atmospheres and what they are made of.

Udry said he and Sasselov would be observing the Gliese system with a Canadian space telescope named MOST to see whether there are any dips in starlight caused by the new planet. Failing that, they said, the best chance for more information about the Gliese system lies with NASA's Terrestrial Planet Finder and the European Space Agency's Darwin missions, which are designed to study Earthlike planets but have been delayed by political, technical and financial difficulties.

"We are starting to count the first targets," Udry said.

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system.

See an animation of the movement of planets in our solar system. See amazing views from space

See amazing views from space